Introduction

First part of this mini-series will focus on more theoretical side of dithering -some history and applying it for 1D signals and to quantization. I will try to do some frequency analysis of errors of quantization and how dithering helps them. It is mostly theoretical, so if you are interested in more practical applications, be sure to check the index and other parts.

You can find Mathematica notebook to reproduce results here and the pdf version here.

What is dithering?

Dithering can be defined as intentional / deliberate adding of some noise to signal to prevent large-scale / low resolution errors that come from quantization or undersampling.

If you have ever worked with either:

- Audio signals,

- 90s palletized image file formats.

You must have for sure encountered dithering options that by adding some noise and small-resolution artifacts “magically” improved quality of audio files or saved images.

However, I found on Wikipedia quite an amazing fact about when dithering was first defined and used:

…[O]ne of the earliest [applications] of dither came in World War II. Airplane bombers used mechanical computers to perform navigation and bomb trajectory calculations. Curiously, these computers (boxes filled with hundreds of gears and cogs) performed more accurately when flying on board the aircraft, and less well on ground. Engineers realized that the vibration from the aircraft reduced the error from sticky moving parts. Instead of moving in short jerks, they moved more continuously. Small vibrating motors were built into the computers, and their vibration was called dither from the Middle English verb “didderen,” meaning “to tremble.” Today, when you tap a mechanical meter to increase its accuracy, you are applying dither, and modern dictionaries define dither as a highly nervous, confused, or agitated state. In minute quantities, dither successfully makes a digitization system a little more analog in the good sense of the word.

— Ken Pohlmann, Principles of Digital Audio

Dithering quantization of a constant signal

quantizedDitheredSignal =

Round[constantSignalValue + RandomReal[] – 0.5] & /@ Range[sampleCount];

Mean[ditheredSignalError]

0.013

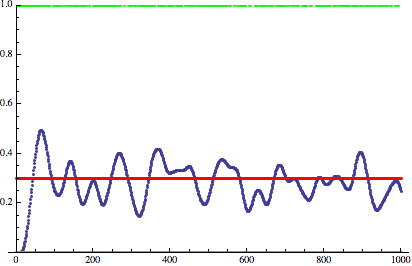

Red plot/spike = frequency spectrum of error when not using dithering (constant, no frequencies). Black – with white noise dithering.

Frequency sensitivity and low-pass filtering

- Increased maximal error.

- Almost zeroed average, mean error.

- Added constant white noise (full spectral coverage) to the error frequency spectrum, reducing the low-frequency error.

- Our vision has a limit of acuity. Lots of people are short-sighted and see blurred image of faraway objects without correction glasses.

- We perceive medium scale of detail much better than very high or very low frequencies (small details of very smooth gradients may be not noticed).

- Our hearing works in specific frequency range (20Hz -20kHz, but it gets worse with age) and we are most sensitive to middle ranges – 2kHz-5kHz.

Therefore, any error in frequencies closer to upper range of perceived frequency will be much less visible.

Furthermore, our media devices are getting better and better and provide lots of oversampling. In TVs and monitors we have “retina”-style and 4K displays (where it’s impossible to see single pixels), in audio we use at least 44kHz sampling file formats even for cheap speakers that often can’t reproduce more than 5-10kHz.

Red – desired non-quantized signal. Green – quantized and dithered signal. Blue – low pass filter of that signal.

Quantizing a sine wave

Low-pass filtered quantized sine

Low-pass filtered quantized sine error

Red – original sine. Green – low pass filtered undithered signal. Blue – low pass filtered dithered signal.

Plotting both error functions confirms numerically that error is much smaller:

Red – error of low-pass filtered non-dithered signal. Blue – error of low-pass filterer dithered signal.

Finally, let’s just quickly look at a signal with better dithering function containing primarily high frequencies:

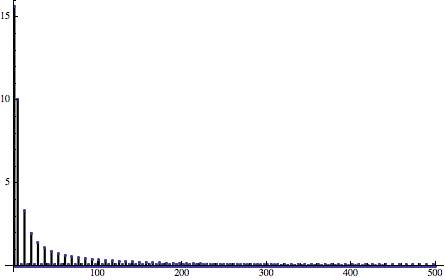

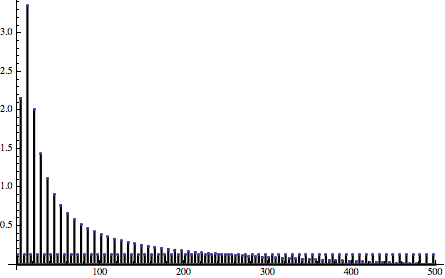

Upper image – white noise function. Lower image – a function containing more higher frequencies.

Low-pass filtered version dithered with a better function – almost perfect results if we don’t count filter phase shift!

And finally – all 3 comparisons of error spectra:

Red – undithered quantized error spectrum. Black – white noise dithered quantized error spectrum. Blue – noise with higher frequencies ditherer error spectrum.

Summary

- Dithering distributes quantization error / bias among many different frequencies that depend on the dithering function instead of having them focused in lower frequency area.

- Human perception of any signal (sound, vision) works best in very specific frequency ranges. Signals are often over-sampled for end of perception spectrum in which perception is almost marginal. For example common audio sampling rates allow reproducing signals that most adults will not be able to hear at all. This makes use of dithering and trying to shift error into this frequency range so attractive because of previous point.

- Different noise functions produce different spectra of error that can be used knowing which error spectrum is more desired.

In the next part we will have a look at various dithering functions – the one I used here (golden ratio sequence) and blue noise.

Pingback: Dithering part two – golden ratio sequence, blue noise and highpass-and-remap | Bart Wronski

Pingback: Dithering in games – mini series | Bart Wronski